The number of scholars targeted for their speech has risen dramatically since 2015, and undergraduates increasingly are to blame, according to a database of these incidents released today by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education.

Undergraduates aren’t the only ones seeking to censor graduate students, instructors, professors and other researchers, FIRE’s database and an accompanying report make clear. But undergraduates’ prevalence within FIRE’s new database concerns the pro-speech group nonetheless.

Komi German, a research fellow at FIRE, said Monday that it’s unclear whether there are more students than ever seeking to “punish” scholars for their speech, or if there are an “emboldened” but relative few. Either way, German said, “it’s a huge red flag for those concerned about students’ tolerance of dissenting views.”

Other would-be censors include politicians and the general public. But threats to scholars’ free speech increasingly originate from within the campus community, not limited to but especially students, according to the report. (The chart below shows incidents over time, by who is initiating them on campus.)

This is far from the first time that FIRE has warned that students represent an increasing threat to free speech on campus. FIRE’s president, Greg Lukianoff, has written or co-written a series of books to this effect, most recently The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, in 2018. But FIRE’s report says the database is “the most comprehensive documentation to date on targeting incidents” at U.S. institutions, from 2015 through July of this year.

This is far from the first time that FIRE has warned that students represent an increasing threat to free speech on campus. FIRE’s president, Greg Lukianoff, has written or co-written a series of books to this effect, most recently The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, in 2018. But FIRE’s report says the database is “the most comprehensive documentation to date on targeting incidents” at U.S. institutions, from 2015 through July of this year.

Increasing Over Time

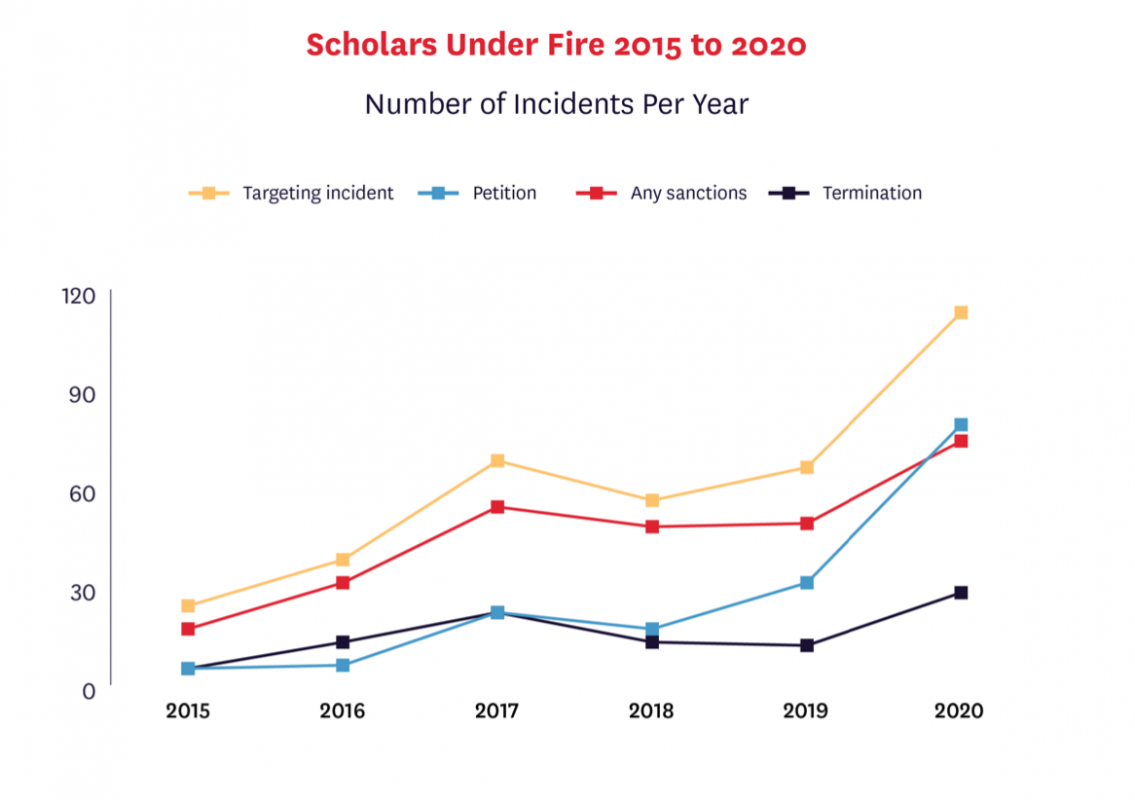

FIRE, which plans to continue adding to the database, so far logs 426 incidents since 2015. Some 74 percent of incidents thus far resulted in some kind of sanction -- including an investigation alone or voluntary resignation -- against the scholar. Suspensions, terminations and other obvious sanctions count, too, of course.

Whereas there were just 24 such incidents in 2015, according to the database, there were 113 in 2020. The first half of 2021 saw 61.

Of the 426 incidents total, 63 percent involved a scholar expressing what FIRE determined to be a personal view or opinion on a controversial social issue. More than 100 incidents involved scholars’ social media.

Half of the incidents involved a scholar’s research or teaching practices, or both.

In 107 cases, scholars were presenting what FIRE describes as “sensitive, controversial and/or difficult content,” such as text containing a racial slur or portraying violence against women, for “purposes of encouraging discussion and learning.” In 106 cases, scholars were discussing scholarship, doing research or offering a "testable hypothesis."

The pedagogical climate is changing and some scholars no longer believe it’s acceptable to require students to read or view triggering content, especially without a warning. But FIRE takes the view that targeting scholars for what they say or do in the classroom or in their research has “the effect of undermining the primary function of academic freedom: to ensure the furtherance of knowledge in American institutions of higher education.”

Scholars were most often targeted for their speech on race, according to FIRE’s analysis. Other hot-button issues were partisanship, gender and campus policies. Targeted scholars tended to study law, political science, English, history and philosophy -- fields that are, alarmingly, to FIRE, “at the core of a liberal arts education” and “routinely discuss and debate what it means to live in a free and open society.”

Scholars were most often targeted for their speech on race, according to FIRE’s analysis. Other hot-button issues were partisanship, gender and campus policies. Targeted scholars tended to study law, political science, English, history and philosophy -- fields that are, alarmingly, to FIRE, “at the core of a liberal arts education” and “routinely discuss and debate what it means to live in a free and open society.”

FIRE defines a targeting incident as a campus controversy involving “efforts to investigate, penalize or otherwise professionally sanction a scholar for engaging in constitutionally protected forms of speech.” A scholar who is harassed for their speech but who didn’t face a professional sanction -- as serious and as real as these cases are -- wouldn’t qualify as a target.

Similarly, a professor who faced professional sanctions for unprotected speech or actions wouldn’t be a target, in FIRE’s view. In one example, FIRE excluded from its database Melissa Click, the former assistant professor of communication studies at the University of Missouri at Columbia who was fired in 2016 for attempting to block student journalists from covering a student protest. Because Click physically obstructed members of the news media from covering a protest, FIRE says, her speech was not protected.

Here, and elsewhere in the report, FIRE differs from groups less focused on First Amendment fundamentals than academic freedom, namely the American Association of University Professors. The AAUP defended Click, if not her actions, to Mizzou and eventually censured the university for not following established disciplinary procedures in her case.

More From the Left

Unsurprisingly, in this increasingly polarized political environment, FIRE determined that many targeting incidents are political in nature. FIRE also found that targeted incidents “come from individuals and groups to the political left of the scholar more often than the political right.”

Sometimes this is something of a guessing game, as in the case of Teresa Buchanan, whom Louisiana State University fired in 2015 for cursing and talking to students about sex in her education classes. The FIRE database says that Buchanan was targeted from the political left, relative to her. She publicly attributed her termination to “political correctness run amok,” but it’s otherwise unclear where this opposition originated. The university said she’d created a hostile learning environment.

German, of FIRE, said that in each case, “we look at the totality of evidence. And it's important to note that we characterize incidents as coming from the right or the left of the scholar.” A scholar on the political left can still be targeted from the left, she said, “and a scholar from the right can be targeted from the right.”

German, of FIRE, said that in each case, “we look at the totality of evidence. And it's important to note that we characterize incidents as coming from the right or the left of the scholar.” A scholar on the political left can still be targeted from the left, she said, “and a scholar from the right can be targeted from the right.”

In any case, Buchanan, as a woman, wasn’t the typical target. According to FIRE, censorship attempts are more often aimed as “scholars who are tenured, white and male.”

Bruce Gilley, a white, tenured male professor of political science at Portland State University, for instance, has been targeted multiple times for his teaching and research, including over a 2017 paper defending aspects of colonialism. These incidents have led to serious professional consequences for Gilley, including the withdrawal of his book on imperialist Sir Alan Burns by its original publisher.

FIRE’s accounting may nevertheless obscure the racial dynamics at play here. Many scholars of color report that they have been targeted for harassment online and even faced death threats for their speech. A recent survey by the AAUP, for instance, found that scholars who were profiled by a conservative website for their “liberal bias” in 2020 were disproportionately Black, and that 40 percent of all those profiled had faced harassment leading up to threats of violence or death. FIRE mentions this survey in its report, and its database includes numerous scholars of color, including sociologist Saida Grundy, whose tweets about race proved controversial when she was an incoming professor at Boston University in 2015. But if the incident FIRE investigated didn’t involve some explicitly professional consequence for the scholar, it was not included in the database.

FIRE is a proponent of the Chicago Principles ensuring campus speech protections. The group found that campuses where the most targeting incidents occurred had “speech-restrictive” policies and were unlikely to have adopted the Chicago Principles, which originated at the University of Chicago. The foundation also recently launched a legal defense fund for targeted scholars.

Questions About Methodology -- and Shared Concerns

To fill the database, FIRE gathered data from news reports and other tracking projects, including the Free Speech Tracker from Georgetown University’s Free Speech Project, the National Association of Scholars’ “Tracking ‘Cancel Culture’ in Higher Education” list and Retraction Watch.

Joerg Tiede, director of research for the AAUP, expressed some concerns about FIRE’s left-right threat methodology. Erlene Grise-Owens, whom Spalding University told to resign in 2016, for instance, had criticized the university for allegedly failing to notify Black faculty members in particular that a student in their department had brought a gun to class. FIRE determined that she’d been targeted from the political right, relative to her. But Tiede called this “bizarre reasoning.” In the same vein, he said, if Buchanan’s left-threat determination is based on the idea that the political left is the “language police,” that’s also suspect.

Joerg Tiede, director of research for the AAUP, expressed some concerns about FIRE’s left-right threat methodology. Erlene Grise-Owens, whom Spalding University told to resign in 2016, for instance, had criticized the university for allegedly failing to notify Black faculty members in particular that a student in their department had brought a gun to class. FIRE determined that she’d been targeted from the political right, relative to her. But Tiede called this “bizarre reasoning.” In the same vein, he said, if Buchanan’s left-threat determination is based on the idea that the political left is the “language police,” that’s also suspect.

Tiede said that the AAUP tends to think of scholars as being “targeted” on social media. He also noted that the AAUP doesn’t consider investigations, which make up the biggest share of FIRE’s logged sanctions, to be sanctions on their own. Summary suspensions pending investigations are sanctions, however, he said.

Crucially, according to widely followed AAUP principles, serious sanctions shouldn’t be contemplated without the involvement of a faculty body, Tiede said.

Despite these criticisms, the AAUP, among other pro-speech groups, has expressed general concern about the climate for scholars’ speech, including for those who discuss race on social media, and with respect to trigger warnings and even Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which makes gender discrimination illegal.

The AAUP’s 2016 report on Title IX, for instance, cited a “frenzy of cases in which administrators’ apparent fears” have overridden faculty academic freedom, along with student free speech rights.

from Inside Higher Ed https://ift.tt/38y2HCt

Comments

Post a Comment