The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill continues to make history in its treatment of Black people.

This month, the university won (at the district court level) a federal suit challenging its use of affirmative action to admit students. The judge in the case ruled the university was appropriately considering students’ races in making admissions decision.

But in the spring, the university declined to award tenure to Nikole Hannah-Jones, an acclaimed New York Times journalist. The university said she could come to the university without tenure -- even though past holders of the chair she would have assumed had been awarded tenure. Hannah-Jones is Black; the board members ruling on her tenure case were white. The university eventually relented on offering her tenure, but Hannah-Jones took another job, at Howard University.

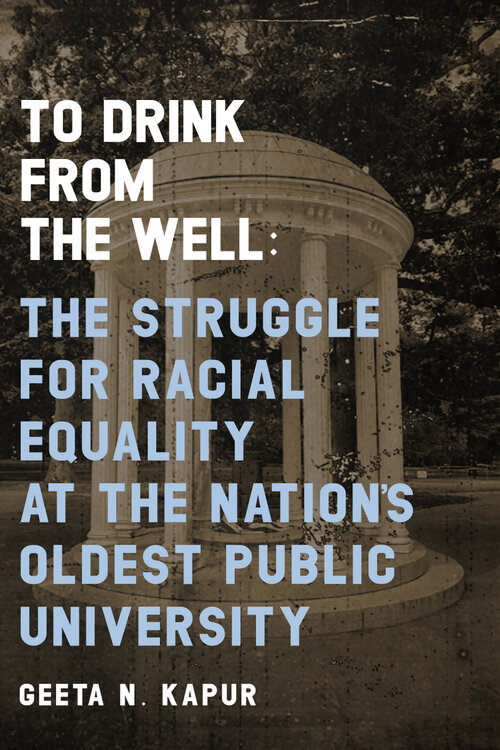

Most of Getta N. Kapur’s new book -- To Drink From the Well: The Struggle for Racial Equality at the Nation’s Oldest Public University -- concerns earlier times. Kapur is a UNC alumna and a civil rights lawyer. She tells the stories of how the university (which dates to the 18th century) used enslaved people to build the university, how the state of North Carolina fought desegregation efforts and how the university delayed efforts to honor Black people and to remove honors for champions of white supremacy.

She responded, via email, to questions about the book.

Q: Would you explain the title of the book -- To Drink From the Well?

A: The Old Well at the University of North Carolina is an iconic symbol around the world. Legend has it if students drink from the well on the first day of class, they will get good grades. NAACP lawyer Conrad Pearson -- who sued the university several times to open its doors to Black North Carolinians -- said this about the Old Well: “That well over there was dug by slaves who I imagine with each stroke of the pick and each scoop of the shovel, they prayed that someday their descendants would drink from the well of knowledge that was the university.”

Q: How did slaves contribute (against their will) to the construction and creation of Chapel Hill?

A: Scores of enslaved people labored in the summer of 1793 clearing a path for the main street of Chapel Hill, Franklin Street, named after Benjamin Franklin. They made bricks on the grounds of the University of North Carolina. Then they built the nation’s first public university building brick by brick. Enslaved people who were rented or owned by university administrators built the next seven buildings, the president’s home and the stone walls that surround the campus.

Enslaved people served and tended to the needs of the students and faculty. They shined shoes, made beds, brought water from the Old Well to the dormitories each morning, cut firewood and made fires and maintained university buildings. They also had the dehumanizing task of emptying slop buckets filled with urine and feces.

Enslaved people contributed to the university in another way. When someone died without a will and without legal heirs, their property passed to the state of North Carolina to be disposed of by the Legislature. The Legislature gave the property to the university to sell. University trustees and university lawyers across the state could search court records and collect escheated property. During slavery this meant chattel property -- enslaved people. The most horrific example I found was that of an elderly Black man who was free and bought his daughter out of slavery. She later had a son. The elderly man died without a will and had no legal heirs. In the wake of Nat Turner’s revolt, making a slave free was illegal, so the woman and the child were her father’s property. The woman and child escheated/passed to the state and were given to the university. Trustees sold the woman and child for cash, claiming slavery was for their benefit. Enslaved people and property were sold this way. Between 1790 and 1840, escheats of Black people and land brought the university $362,390 ($9.4 million today) -- 69 percent of its total revenue.

Q: How did Black people come to be admitted to Chapel Hill?

A: In 1951, four law students from the all-Black North Carolina College for Negroes -- Floyd McKissick, Solomon Revis, James Lassiter and Kenneth Lee -- applied to the white law school at the University of North Carolina. Though they were North Carolina residents and their parents paid taxes to support the university, they were denied admission. They sued. They won and were admitted to the all-white law school in June of 1951.

In the fall of 1955 -- a few months after the second U.S. Supreme Court opinion in Brown v. Board of Education -- three young Black men from Hillside High School in Durham, N.C., applied for admission to the University of North Carolina. University officials took the position that the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown -- segregated schools were inherently unequal and unconstitutional -- did not apply to colleges and universities. The applications were denied. The three sued for admission to the white school. After a lengthy court battle that ended in the U.S. Supreme Court, the three young men prevailed and were admitted to the nation’s oldest public university.

In both cases, the university begrudgingly admitted the Black men. They were not welcomed. Instead they were segregated to live on the third floor of Steele dormitory and were not allowed to sit in the student section at football games. They were not provided academic support. One put it aptly when he said, “I failed. And the university failed.”

Q: How did UNC handle the debates over Silent Sam, a Confederate monument on campus, and other named monuments that offended people who are aware of Jim Crow? And how did the university serve Black students?

A: An opening quote in my book reads, “History will reveal that at no time has the oppressors of a people ever voluntarily lifted their heels from the necks of the oppressed and that it has only been through ‘push’ struggle or force that oppressed people have been able to move toward the goal of free men.” This is so true of the nation’s oldest public university. It has only acted after struggle and being forced to do so.

In 1983, the university acknowledged the need for a Black Cultural Center, in large part because of the efforts of Sonja Haynes Stone. A feasibility study done by the university said the center would need at least 23,000 square feet. The trustees did not approve of this. The idea languished for five years. Then the trustees shoved the Black Cultural Center into a 900-square-foot space in the student union. While fighting for a Black Cultural Center, Stone was also battling the university to grant her tenure. In the process, she suffered an aneurysm and died in 1991. Her death became the catalyst for a freestanding building for the Black Cultural Center. Students began mounting pressure upon university officials through protests. Four star football players threatened not to play football. In one protest students sat down on the floor of Chancellor Paul Hardin’s office and refused to leave. They were arrested. This made national news, bringing the Reverend Jesse Jackson and famed movie director Spike Lee to Chapel Hill. In 1993 the Board of Trustees relented and approved a freestanding Black Cultural Center but told supporters they would have to raise all the money to build it. It took supporters eight years to raise the several million dollars. And in 2004 -- 21 years after the struggle began -- the Sonja Haynes Black Cultural Center opened.

Students had been protesting since 1965, during the civil rights era, for the removal of the university’s Confederate monument Silent Sam. The statue was erected by the university in 1913. After the deadly protest in Charlottesville, Va., students took matters into their own hands and toppled the Confederate monument. Afterward, the university Board of Governors made a back-door deal with the Sons of the Confederacy for $2.5 million for the statue and its upkeep. This made national news, bringing condemnation and shame upon the University of North Carolina. Students, faculty and prominent alumni protested to the court, saying the back-door deal damaged the university’s liberal reputation and underscored its commitment to white supremacy. The judge voided the settlement, and Silent Sam was returned to the university.

In yet another instance, a majority of university buildings are named after avowed enslavers and white supremacists who openly used their power, wealth and influence to oppress and murder Black North Carolinians. The building named after William Saunders, the director of the Ku Klux Klan in North Carolina, was changed by the Board of Trustees in 2015. However, the board enacted a 16-year moratorium on renaming campus buildings, monuments, memorials and landscapes. Only after the police murder of George Floyd in May of 2020 -- when the nation was in an uproar and in a moment of inflection about the role that race and racism play in American society -- the trustees lifted a moratorium on changing building names and took down name plaques of a few university buildings. However, many white supremacist names remain on campus buildings.

Q: How were you treated as an undergraduate and law student at Chapel Hill?

A: My experiences as an undergraduate and a law student were marked by isolation, stress and awareness that I was the other -- an immigrant, a woman and a racial minority. I felt a great deal of pressure to prove that I belonged. I will never forget the comment another law student made to me: “You are a minority. You should use affirmative action to your benefit.” He did not know my grades were high. He just assumed I was there because of affirmative action. That really hurt. It still does and always will.

from Inside Higher Ed https://ift.tt/3blPNcl

Comments

Post a Comment